Evers’s Department of Workforce Development likes to boast about low unemployment rates and high labor force participation, but how is Wisconsin’s economy really doing?

How is Wisconsin really doing? Short answer: Wisconsin is not okay and is getting worse. Compared to the rest of the United States, Wisconsin’s economy is right in the middle of the pack, but this is nothing to write home about. The unemployment rate is significantly lower than the national average, but unemployment figures are notoriously inaccurate and fail to draw a complete picture. With respect to the measures that really matter, Wisconsin is not doing well.

In 2023, rGDP growth was only .2% in Wisconsin compared to the U.S. average of 2.5%. The year prior, Wisconsin grew at .4% while the U.S. grew at 1.9%. Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota and Iowa all grew at rates five times higher than Wisconsin last year and all except Iowa (whose economy shrank by .3%) grew three times faster than Wisconsin in 2022.

Prices in Wisconsin tend to be about 7% lower than the national average, but wages also tend to be lower. Compared to its four neighbors, per capita personal income in Wisconsin is right in the middle at $69,000. Minnesota has the highest income in the region at $72,000 while Michigan has the lowest at $60,000.

Meanwhile, increases in the average price of single-family homes in Wisconsin is far worse than the national average. Since January 2019, the median listing price has increased by 175% while prices have increased by “only” 153% nationwide. Compared to its neighbors, Wisconsin has the worst housing price increases of all midwestern states.

National Employment Data

In a recent report, the MacIver Institute wrote about the possibility of a recession in 2024. That report noted a number of important indicators that predict recession: the inversion of the yield curve; the New York FED’s Recession Probability index; the Conference Board’s LEI; government jobs as a share of all new jobs; and the number of people in the labor force with multiple jobs. This report focuses on the composition of the labor market and uses the most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

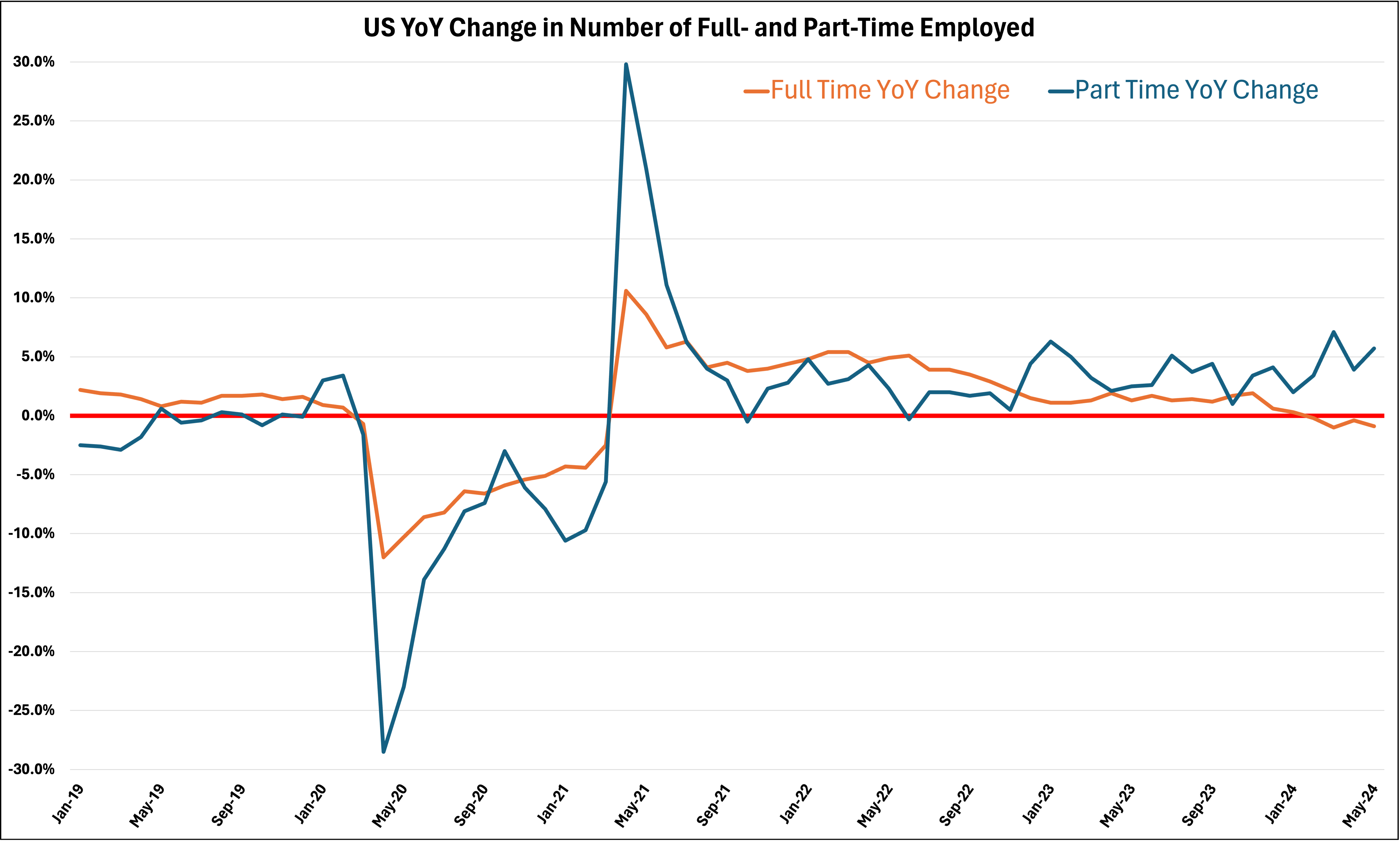

The first indication that the labor market is in poor health is the share of full- and part-time jobs. Since January of this year, the U.S. has not created a single full-time job. What’s worse, the U.S. has lost full-time jobs every single month since the start of the year—jobs that have been entirely replaced by part-time work.

Historically, whenever the year-over-year change in full-time jobs is negative and stays negative, a recession follows shortly after. In February, the number of full-time jobs was .3% lower than it was twelve months prior; in May, full-time jobs were 1% lower than twelve months ago. So far in 2024, there have been four continuous months where full-time employment was negative.

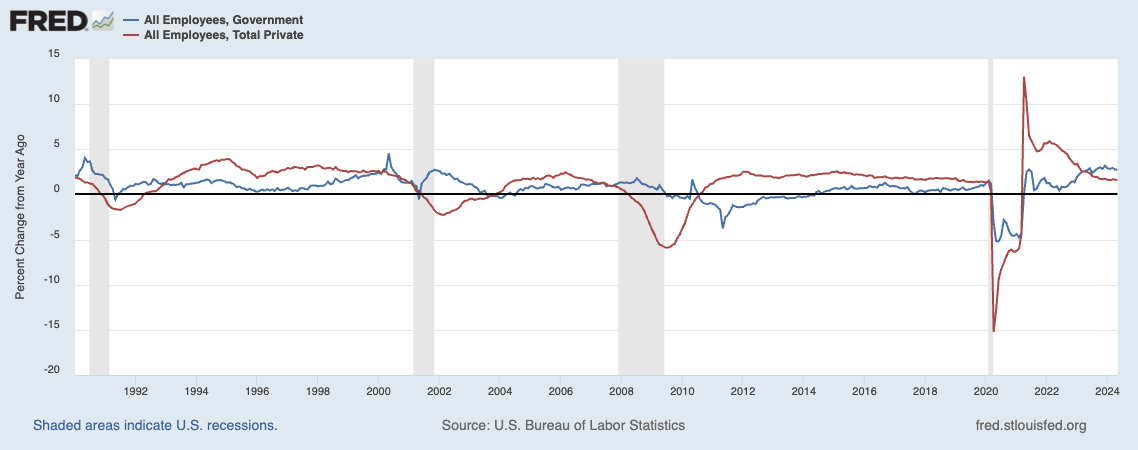

Government’s share of new jobs is also of interest here. Whenever government jobs account for a large portion of all new jobs, recession follows. This is demonstrated by the blue line (government jobs) overtaking the red line (private jobs) in the graph below.

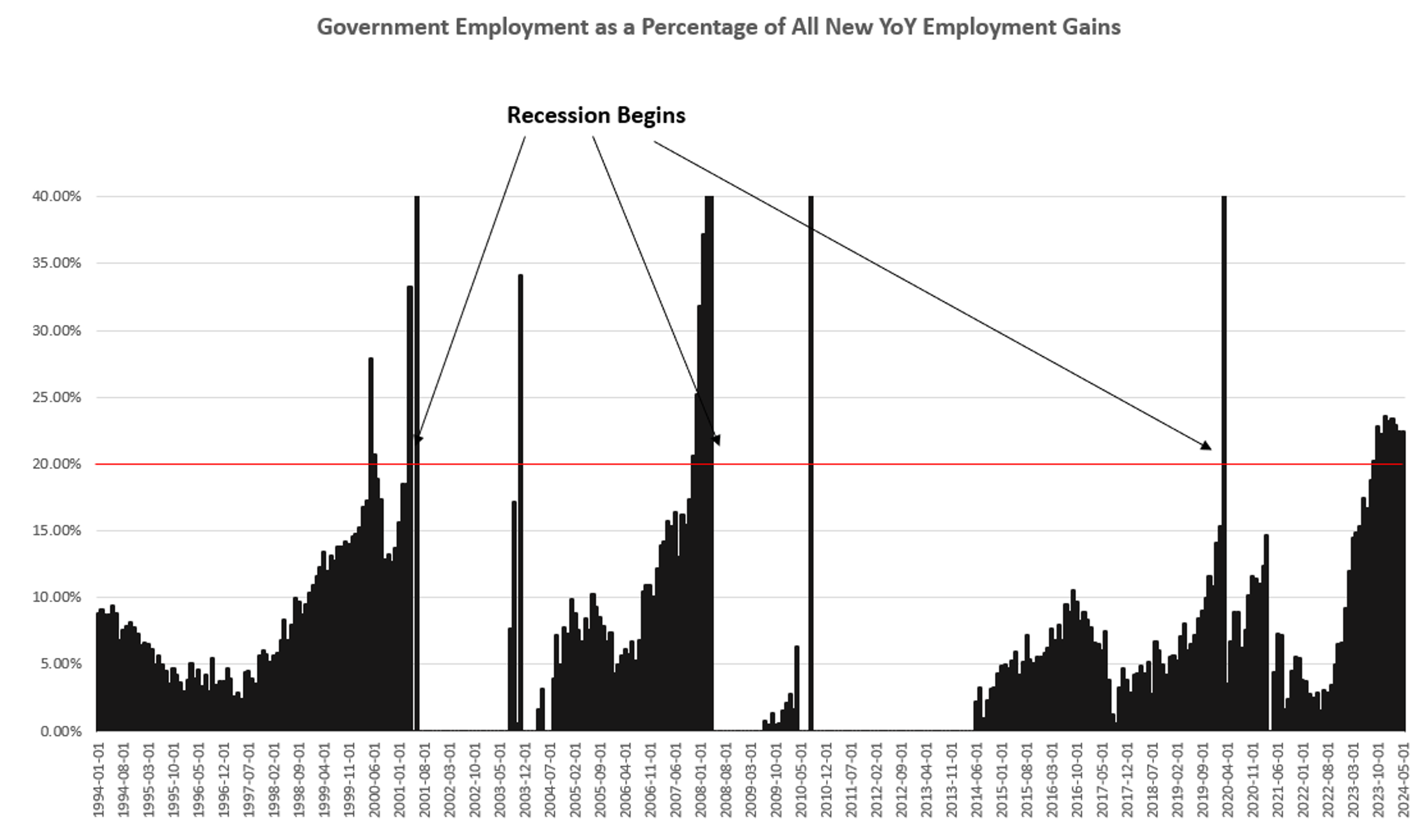

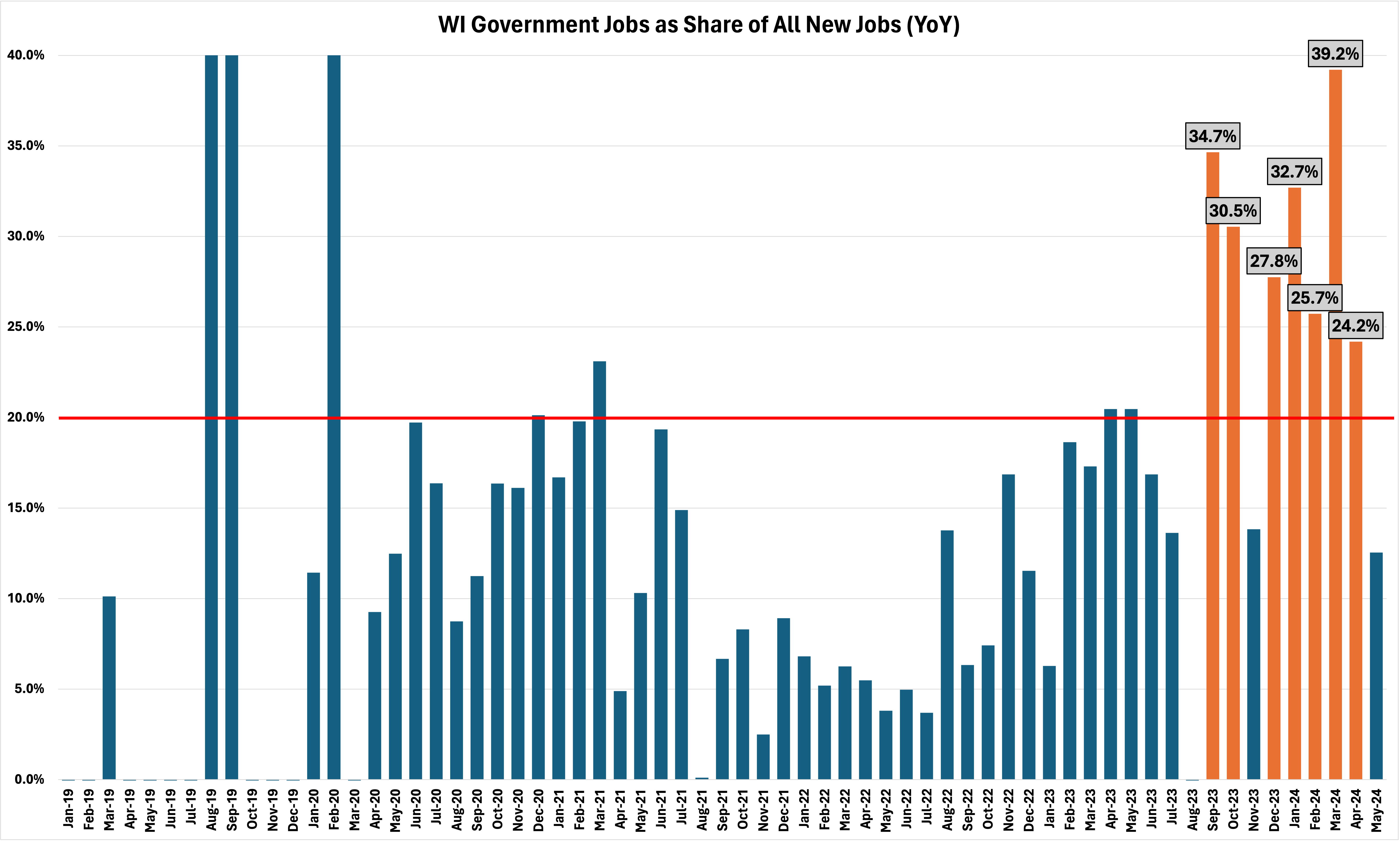

Specifically, as has been pointed out by Ryan McMaken, recession follows when government’s share exceeds 20% of all new jobs. The rapid growth in government employment is a sign that private-sector opportunities are dwindling. This indicates a stagnant or shrinking real economy. Every month since September of 2023 has entailed government jobs accounting for more than 20% of all new jobs (see graph below).

Wisconsin Employment Data

The same phenomena can be seen in the Wisconsin labor market. Although part-time and full-time data are not available, the BLS does report the average number of weekly hours per employee by industry. They also report the number of government and private-sector jobs.

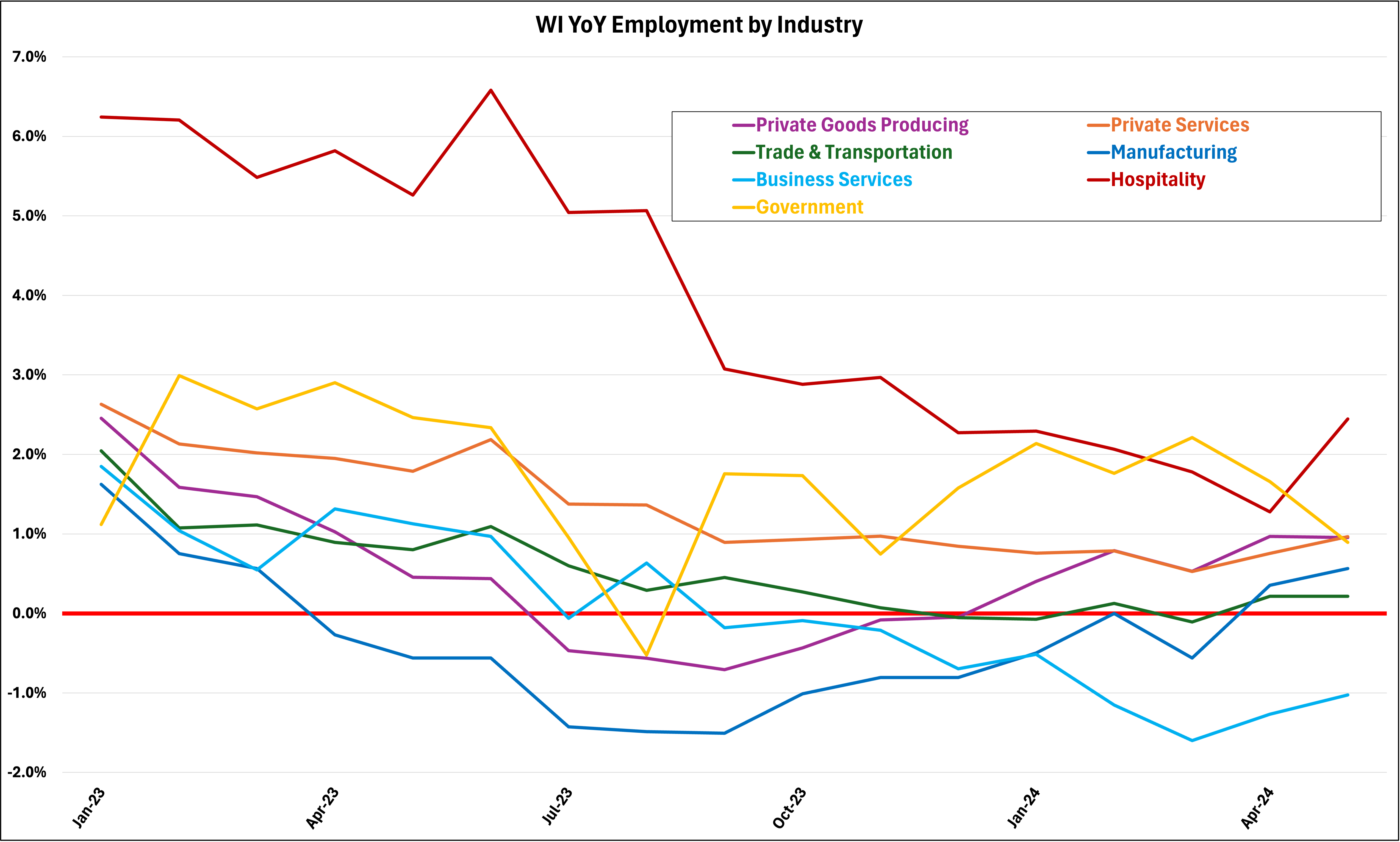

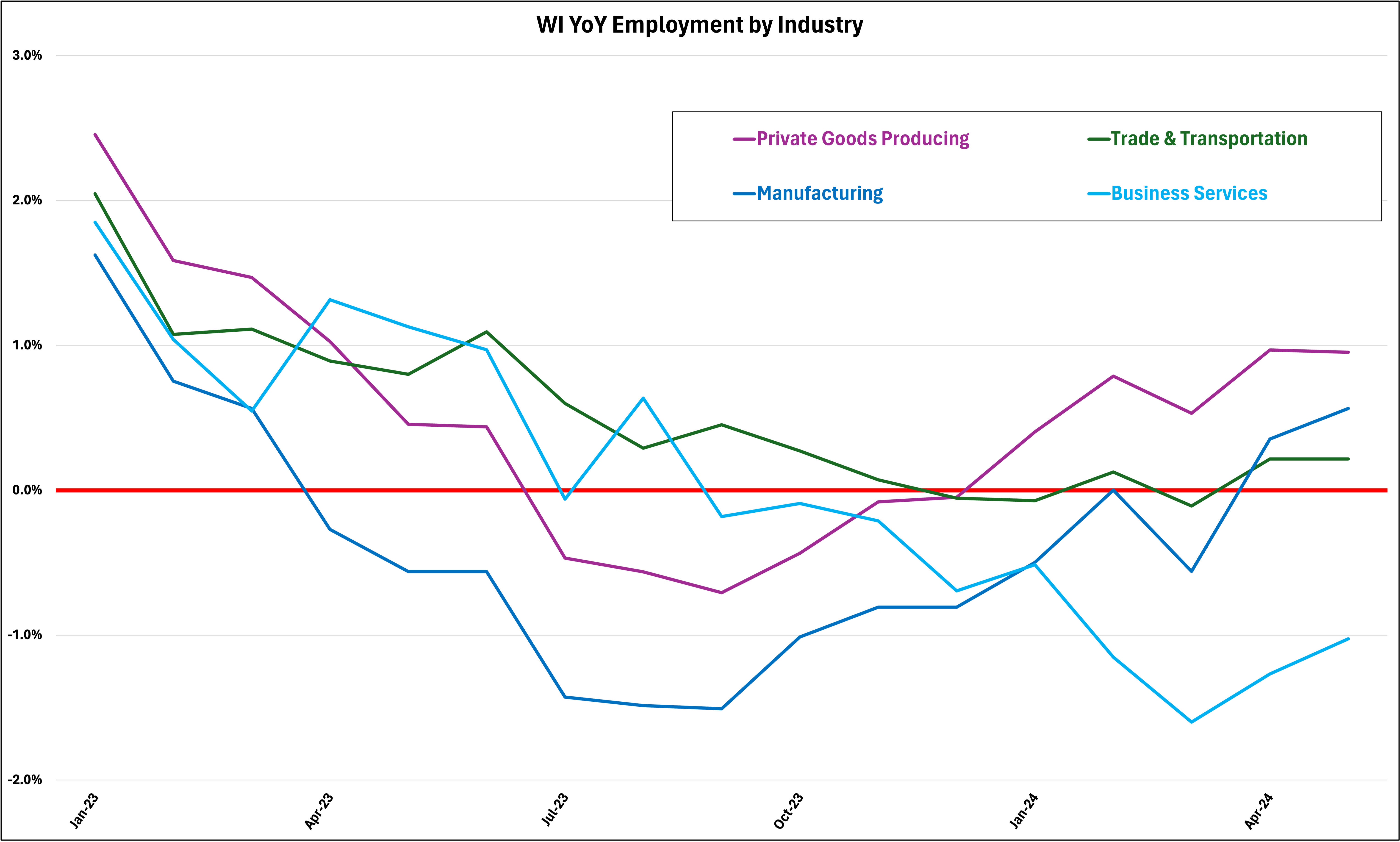

Here in Wisconsin a significant portion of the labor market has seen their hours reduced, indicating that the share of part-time jobs has decreased significantly in the last year. The most impacted industries have been Business Services, Private Goods Production and Manufacturing. Hospitality has faired the best, and also indicates a likely shift to part-time work since restaurants and leisure-oriented firms tend to employ mostly part-time shift work.

If we focus, however, on Business Services, Private Goods Production and Manufacturing, we can see that each suffered serious employment losses over the last year and a half. Manufacturing saw the largest decrease in employment with net job losses occurring every single month for an entire year; the Business Services industry has lost jobs every month since September of 2023 and does not show any signs of recovery; and Private Goods Production saw net job losses for five months from September 2023 to January 24’.

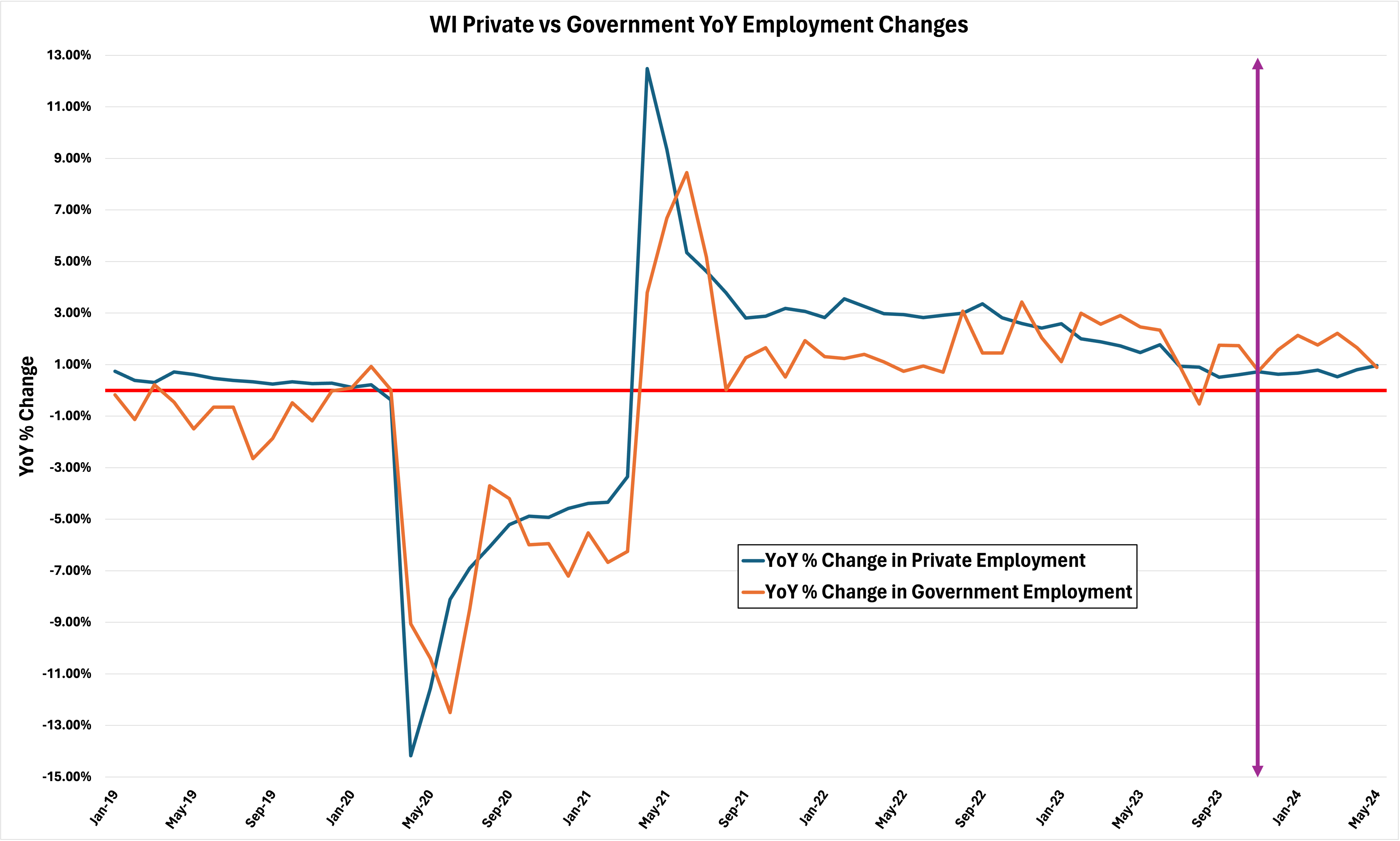

These industries are incredibly significant in Wisconsin since, together, they account for more than half (54%) of all private employment in Wisconsin. Goods Production alone is nearly 24% of total private employment and Manufacturing is 18%. To further complicate the private job market, government jobs in Wisconsin are also accounting for a greater and greater share of all year-over-year job growth. This indicates that opportunities in the private sector are limited, and that job-seekers feel there is better financial and job security in the public sector.

For example, the rate at which government employment has been growing in Wisconsin has overtaken the rate of growth in the private sector. Since September 2023 year-over-year government job growth has surpassed the private sector.

Viewed as a share of all new jobs created on a year-over-year basis, Wisconsin’s public sector, like the nation at large, has accounted for well over 20% of all new year-over-year employment gains in seven of the last nine months.

Labor’s shift from private to public-sector work can only be the result of private sector job losses. Despite the DWD’s many reports of “record high employment,” and “record high nonfarm jobs,” these reports fail to give an honest account of Wisconsin’s economy. The best available data from the BLS’s BED report and their QCES survey (which surveys 20 times more businesses than the Establishment Survey the DWD relies on) tell a very different story. In fact, they tell a story of job loss, not growth.

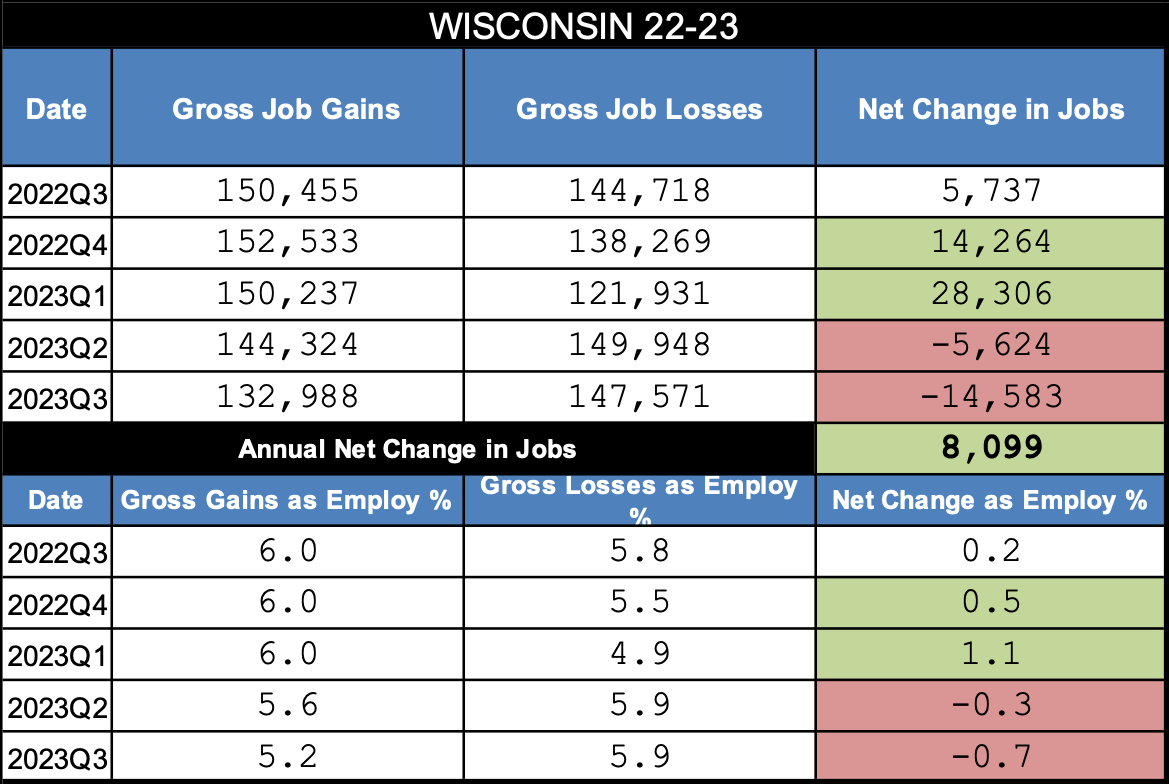

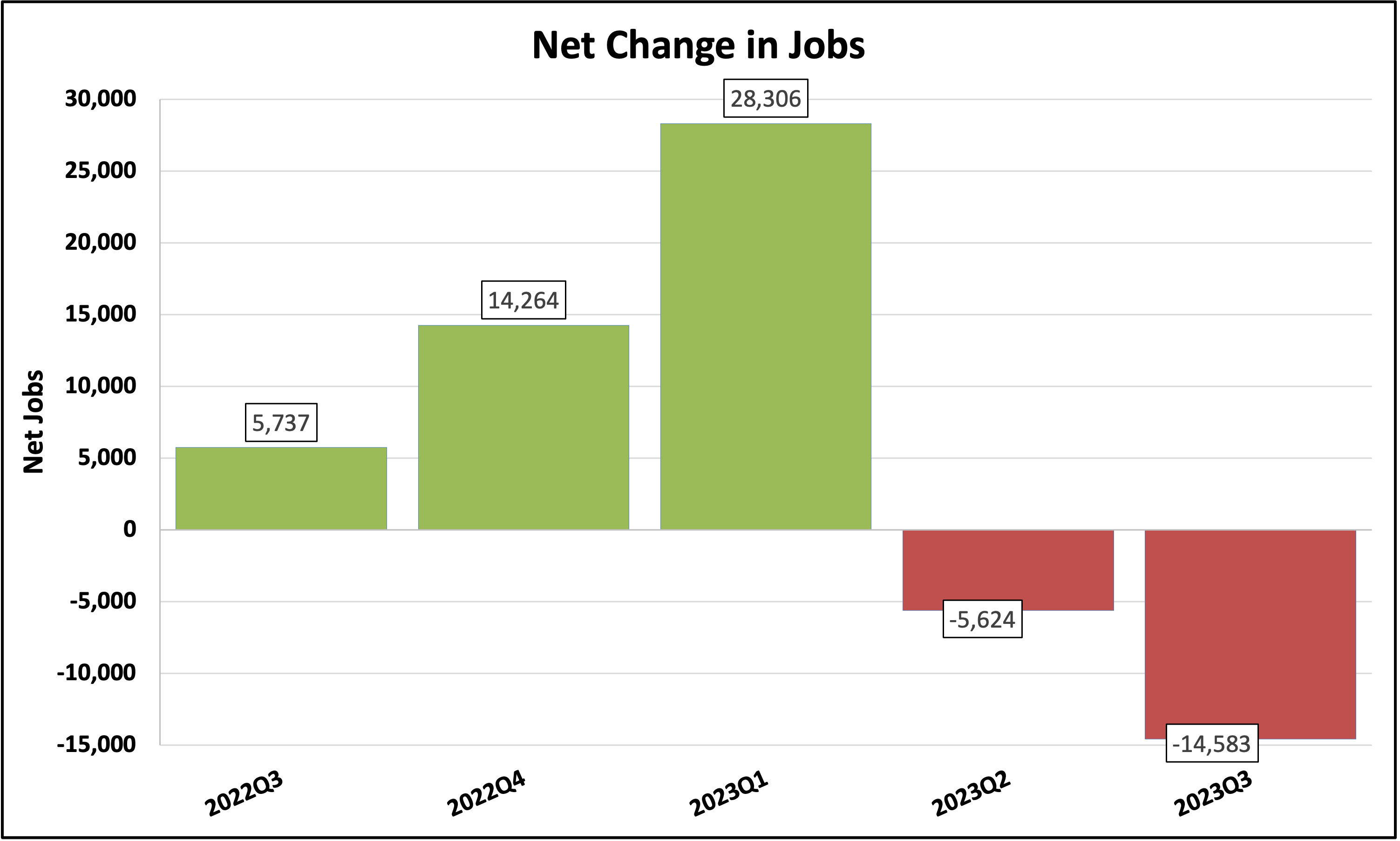

The loss of jobs over the past year can be more easily seen by referring to the BLS’s QCES survey—a lagging indicator of the economy that is among the most accurate and comprehensive surveys of the marketplace. According to data from that survey, Wisconsin gained a net total of 8,099 jobs from 2023Q1-Q3 (Q4 data is not available yet). However, in the second and third quarters, Wisconsin lost a net total of 20,207 jobs.

If these kinds of job losses persist in the Q4 data, it will be enough to eliminate all the job gains from Q1. It is important to note that while perturbations in the job market are normal, it is also normal to expect net gains in every quarter. Yet these graphs show that there were two consecutive quarters’ worth of net losses.

Q2 and Q3 on their own eliminated more than 70% of the job gains in Q1, and there is good reason to believe that Q4 will also show net job losses for Wisconsin given the reduction in average hours worked by private-sector employees and the growth of government jobs.

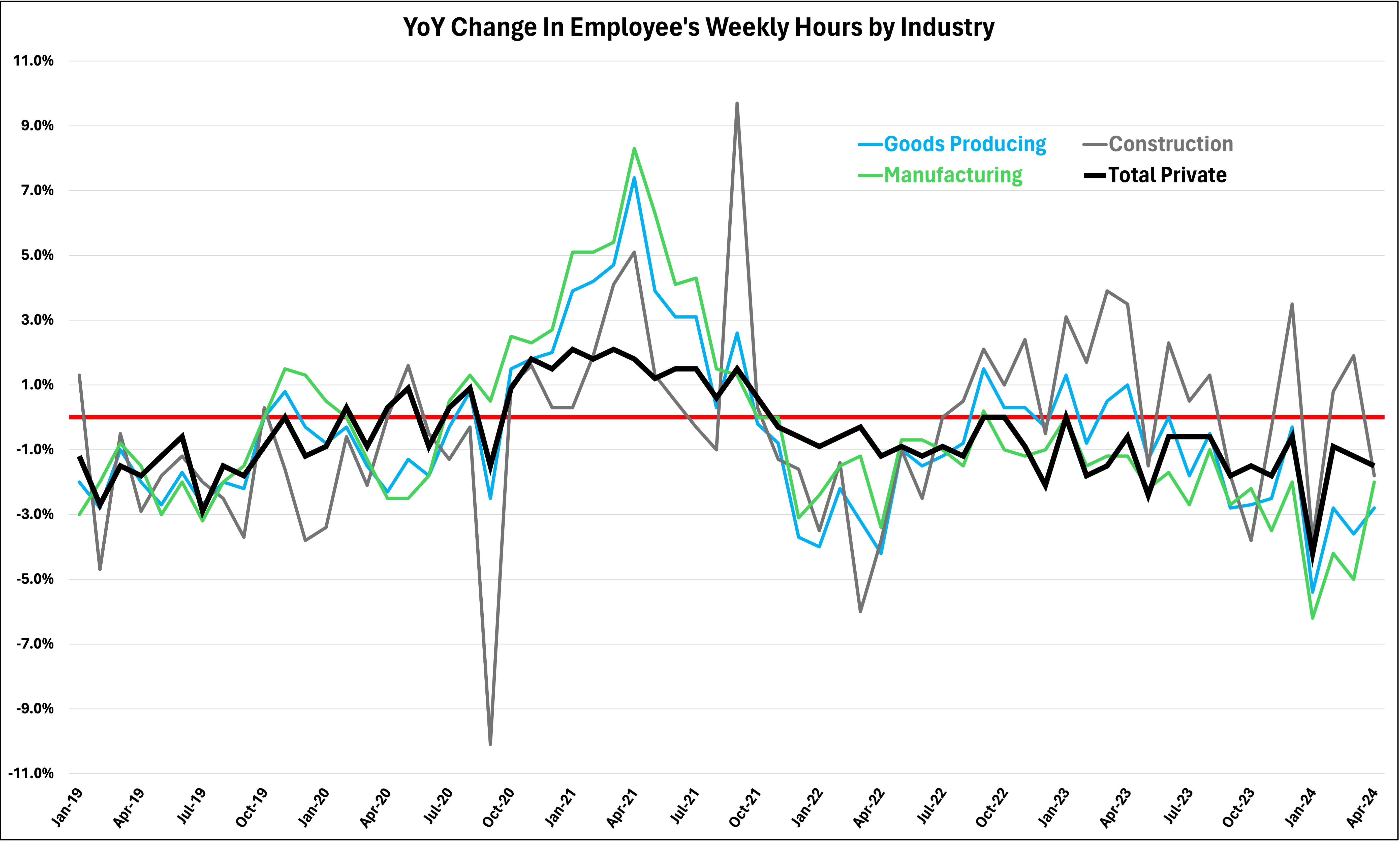

With respect to reduced working hours, just as full-time jobs were replaced by part-time jobs at the national level, labor data for Wisconsin show a similar shift toward part-time work. On average, all private-sector employees have worked fewer hours, every month, from November 2021 through April 2024.

As expected, the Goods Producing and Manufacturing industries have seen the largest decline in average number of hours worked per employee. That Wisconsin should recover from the state’s imposition of a lockdown in October 2020 is expected; but that it should begin to decline to lockdown-level rates only a year later—and persist at that level for two and a half years—is something few could predict.

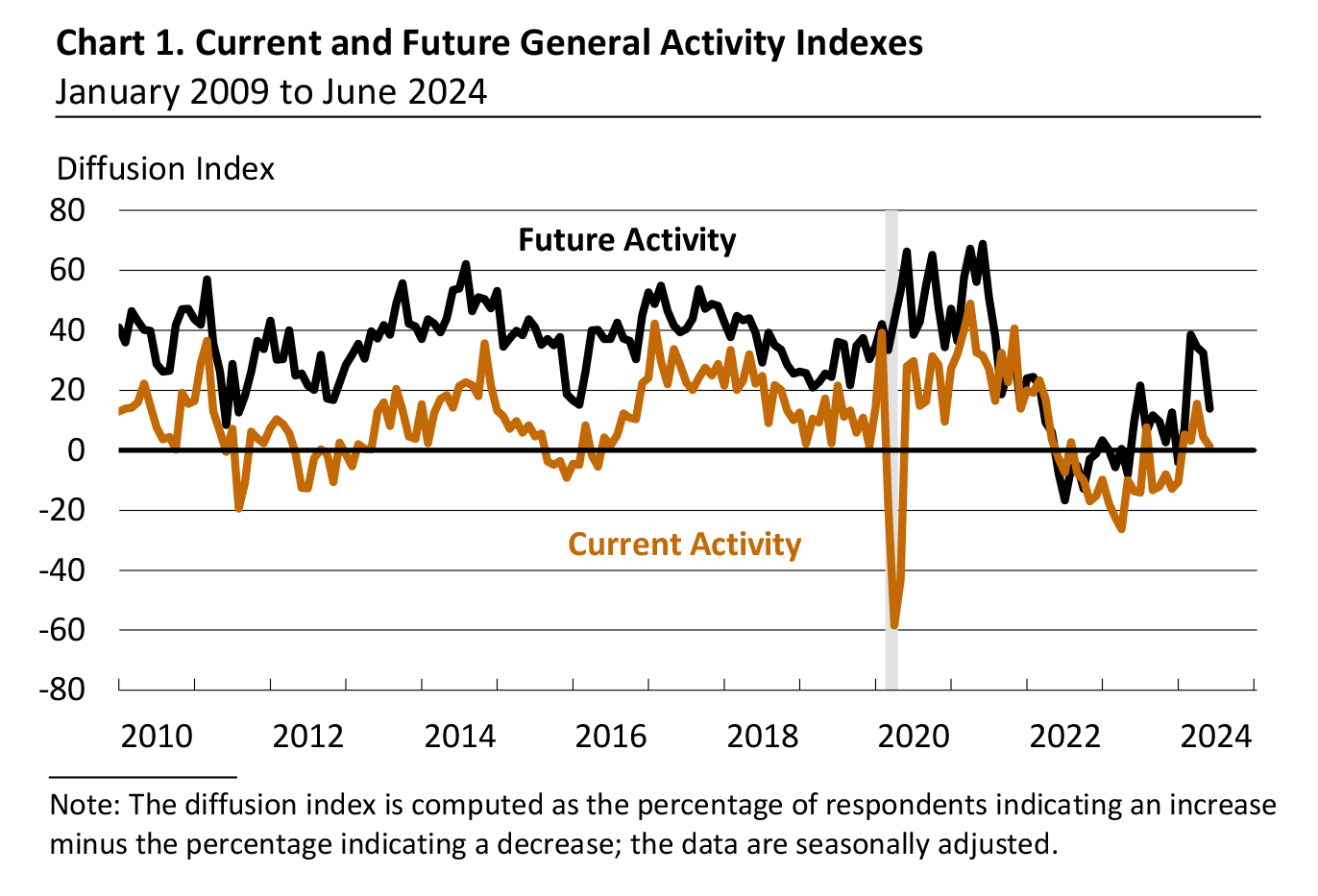

The Philadelphia FED’s Manufacturing Survey in June also demonstrates the trouble facing manufacturing in Wisconsin. According to the survey results, 50% of respondents expect their total 2024:Q2 production to stay the same or decrease. The only silver lining for American manufacturing at the moment is that the new year finally broke the two-year trend of negative manufacturing activity.

Rather unfortunately, it appears that since June, manufacturing activity has again reached “zero” on the activity index.

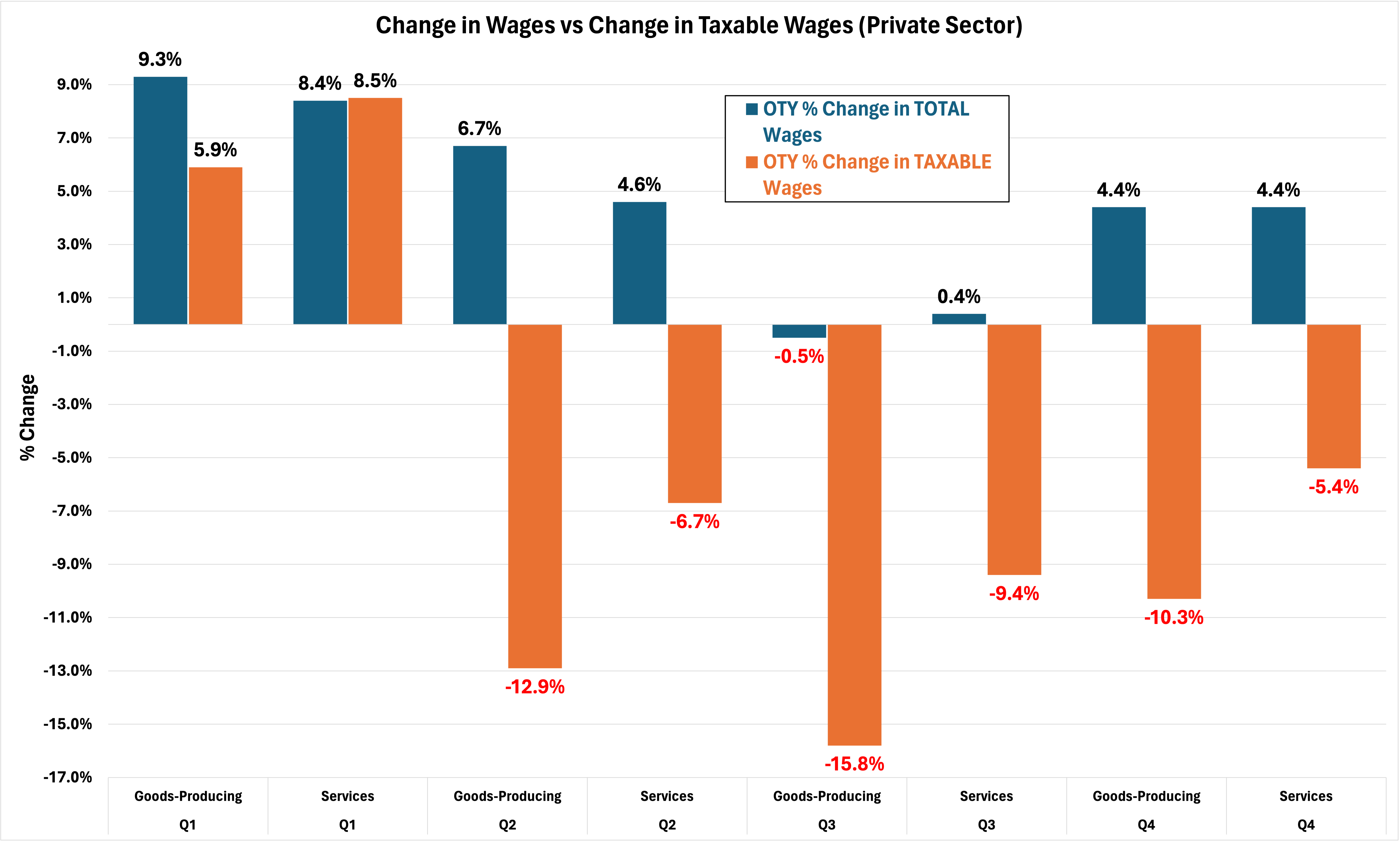

Another interesting datum from 2023 which corroborates Wisconsin’s shift to part-time work is the following graph. This graph shows the year-over-year change in total wages paid in Wisconsin to all private employees versus total taxable wages.

The increase in total wages (that is, the aggregate of all wages paid and not per capita wages) is explained in large part by the high levels of inflation and their effect on prices, generally. The decrease in taxable wages, however, indicates that income-earners in Wisconsin are falling into lower and lower tax brackets—both state and federal. In short, the total dollar amount paid out in wages increased in 2023 while per capita tax burdens decreased because employers were forced to cut the hours of employees in order to accommodate higher labor costs.

Looking more broadly at overall economic activity, the Atlanta FED has predicted real GDP growth of 3% nationwide for 2024:Q2. The Blue Chip Consensus, on the other hand, expects 2% growth. Real GDP in the first quarter of this year was 2.88%, down from 3.13% in 2023:Q4. Economic growth in the Midwest, on the other hand, looks less optimistic.

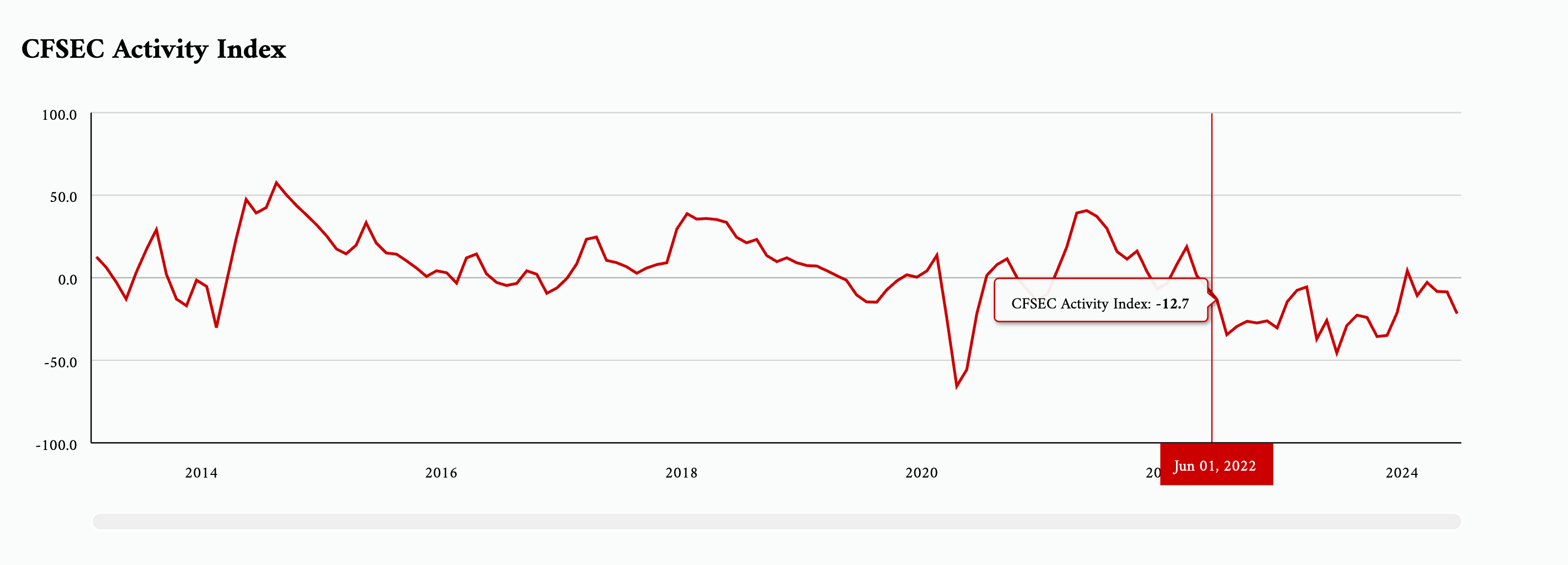

Most of Wisconsin falls within the seventh Federal Reserve district managed by the Chicago FED. In their Survey of Economic Conditions (CFSEC)—a survey of only businesses in the Midwest—respondents in the seventh district reported that their outlook for economic activity was one of contraction, not growth.

Since April of 2022 this index has shown that a majority of survey respondents have reported that they either expect or are experiencing contraction in their businesses. With the exception of just one month in 2024, this index has been negative in 25 of the 26 months since April 2022.

The final point of concern for Wisconsin (and the nation) is the problem with the commercial real estate industry. Since lockdowns ended commercial real estate has been in dire straits. Several high profile properties have already sold for huge discounts in places like New York and Los Angeles, and much more is to come. The reason for this situation and its implications is explained at length in a soon-to-be-released report by the MacIver Institute, but the short explanation is that the banking industry took advantage of the low interest rate environment created by the FED and bet heavily on commercial properties. Due to rising interest rates and lack of demand for commercial real estate (CRE), banks with portfolios that are heavily invested in CRE are at huge risk of collapse.

In 2024:Q1 the FDIC added 11 banks to its so-called “Problem List”, a list of 63 banks the FDIC deems to be at risk of financial collapse. The FDIC reported that these 63 banks have total unrealized losses amounting to more than half a trillion dollars. But other banks are of equal or similar risk of collapse should their CRE loans enter into default or experience high levels of delinquency. If either of those things happen to a significant extent, depositors could “run” on those banks, making them unable to fulfill their liabilities and therefore becoming insolvent.

Wisconsin is of interest in this regard because the Associated Bank is one such bank at risk of collapse. The Associated Bank of Green Bay, WI is the 50th largest bank in the U.S. and has 191 locations in three states—135 of which are located in Wisconsin. Florida Atlantic University (FAU) created a dashboard that evaluates the CRE holdings of the 157 largest banks in the U.S. They measure each bank’s “exposure” to CRE loans by calculating the ratio of CRE loans to the bank’s equity: “Any ratio over 300% is viewed as excessive exposure to CRE,” according to FAU.

Of the 157 banks analyzed by FAU, the Associated Bank ranked 79th for highest exposure to CRE and had a CRE to equity ratio of 271%. When 67 banks have CRE-equity ratios of more than 300%, despite most banks in the U.S. not being anywhere near this threshold, the reader will remember that financial crises do not require that every financial institution make the same mistake to result in widespread economic collapse.

Conclusion

Given the latest available data provided by the BLS, the MacIver Institute believes that the Wisconsin economy is, at best, stagnant but likely on the decline. The decrease in average working hours, the lack of real GDP growth, the increase in the share of government jobs, significant declines in employment in Wisconsin’s most significant industries, and negative values in surveys of Wisconsin businesses all indicate that the real Wisconsin economy is not something to brag about.